I leave this at your ear for when you wake

Oliver, Swensen, Rilke, Murray, Vang, Graham, Adnan

The poetry room is surely the least browsed of the bookshop’s spaces. There are good reasons for this beyond the general idea that poetry is inscrutable by nature.

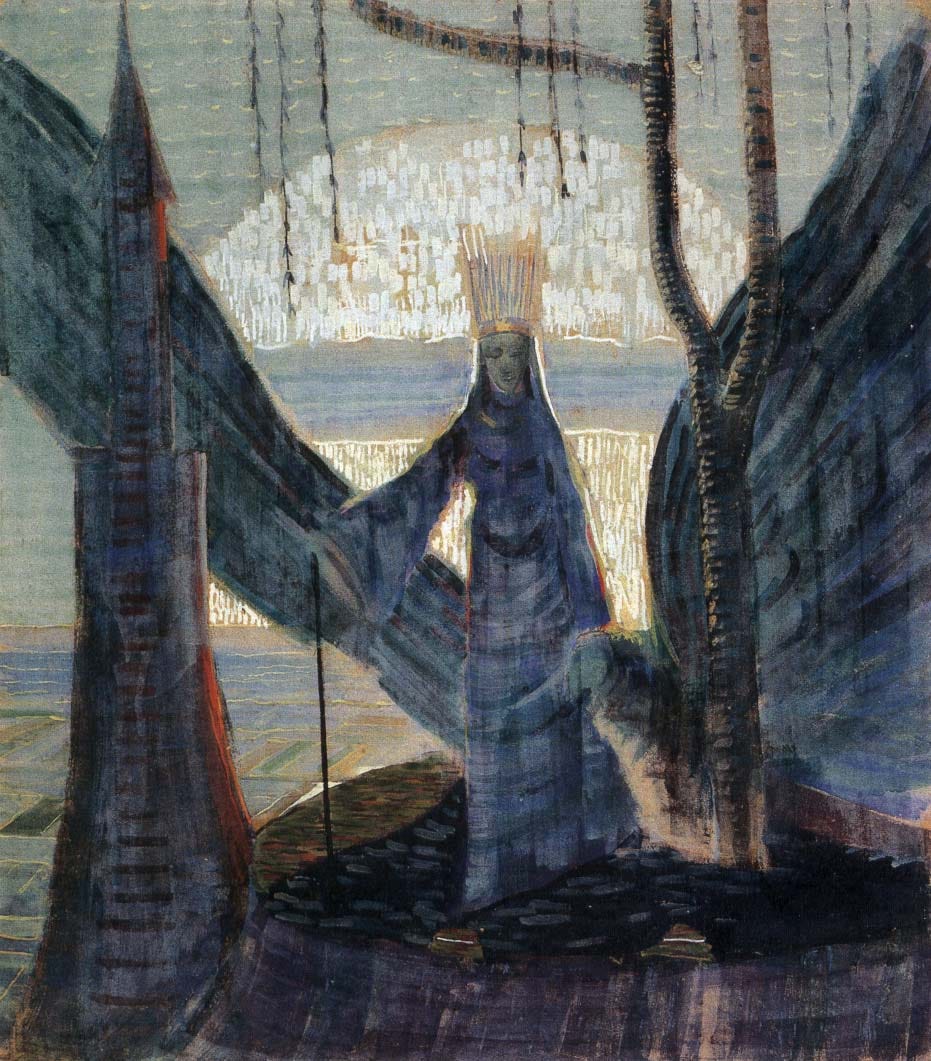

For one, the titles are mostly slim, possessing difficult-to-discern spines that make strict alphabetization futile and lend the shelves an aura of wanton impenetrability. Add to this the fact that within a given linear foot of poetry books you might encounter almost any subject known to the human mind, and said aura shape-shifts into a manifold floodlight pitched straight into your eyeballs. Lastly, and most ironically, the chateau-style light fixture I suspended from the ceiling has the luminosity of a firefly, and it is manifestly difficult to read by phosphorescence.

Given the above and the market for literature in general, poetry is the least lucrative material in this less-than-lucrative business. Yet I pay more attention to it than to any other genre in the shop. Why, besides my pathological affinity for things weird and wayward, is this the case?

Because poetry, in all its unruliness, obscurity, and monomania, is closest to the heart of what personhood is. If a bookshop doesn’t admit of the auric and the odd, the cryptic and cathartic rhythms of idiosyncrasy, then it lets us settle for the typical—the false idea that life can be reduced to a series of types.

Poetry knows better. The alphabet is not a life sentence; genre is a wave. We press on into infinite space with our finite selves. Each of us, like every letter ever written, is cradled by time, in which all things are possible, and nothing is complete.

Dreamwork by Mary Oliver

I rise

by lamplight and hurry out

to the bay

where the gulls like white

ghosts swim

in the shallows—

I rake and rake

down to the gray stones,

the clenched quahogs,

the deadweight

fruits of the sea that bear

inside their walls

a pink and salty

one-lunged life;

we are all

one family

but love ourselves

best. Later I sit

on the dawn-soaked shore and set

a thin blade

into the slightly

hissing space between

the shells and slash through

the crisp life-muscle; I put

what is in the shell

into my mouth, and when

the gulls come begging

I feed them too.

How detailed and hopeful,

how exact

everything is in the light,

on the rippling sand,

at the edge of the turning tide—

its upheaval—

its stunning proposal—

its black, anonymous roar.

Goest by Cole Swensen

I’m on a train, watching landscape streaming by, thinking

of the single equation that lets time turn physical,

equivocal, almost equable on a train

where a window is speed, vertile, vertige. It will be

one of those beautiful equations, almost visible, almost green. There

in the field, a hundred people, a festival, a lake, a summer, a

hundred thousand fields, a woman

places her hand on the small of a man’s back in the middle of the crowd

and leaves it.

New Poems by Rainer Maria Rilke, trans. by Stephen Mitchell

Suddenly, from all the green around you,

something—you don’t know what—has disappeared;

you feel it creeping closer to the window,

in total silence. From the nearby wood

you hear the urgent whistling of a plover,

reminding you of someone’s Saint Jerome:

so much solitude and passion come

from that one voice, whose fierce request the downpour

will grant. The walls, with their ancient portraits, glide

away from us, cautiously, as though

they weren’t supposed to hear what we are saying.

And reflected on the faded tapestries now:

the chill, uncertain sunlight of those long

childhood hours when you were so afraid.

New Selected Poems by Les Murray

Religions are poems. They concert

our daylight and dreaming mind, our

emotions, instinct, breath and native gesture

into the only whole thinking: poetry.

Nothing’s said till it’s dreamed out in words

and nothing’s true that figures in words only.

A poem, compared with an arrayed religion,

may be like a soldier’s one short marriage night

to die and live by. But that is a small religion.

Full religion is the large poem in loving repetition;

like any poem, it must be inexhaustible and complete

with turns where we ask Now why did the poet do that?

You can’t pray a lie, said Huckleberry Finn;

you can’t poe one either. It is the same mirror:

mobile, glancing, we call it poetry,

fixed centrally, we call it a religion,

and God is the poetry caught in any religion,

caught, not imprisoned. Caught as in a mirror

Afterland by Mai Der Vang

I once carried my mollusk tune

All the way to the lottery of gods.

Rain was the old funeral choir

That keened of a hemisphere

Moored under lampwings.

Clouds never left. I knew

The lights would shine clearer

If I closed my eyes, just as

I knew the Pacific would teach

Me to sleep before tying my

Name to the flaming. Here I

Am now at the end of amethyst,

Drizzling another lost sunrise

Inside the quilt of my hand.

New Collected Poems by W. S. Graham

I leave this at your ear for when you wake,

A creature in its abstract cage asleep.

Your dreams blindfold you by the light they make.

The owl called from the naked-woman tree

As I came down by the Kyle farm to hear

Your house silent by the speaking sea.

I have come late but I have come before

Later with slaked steps from stone to stone

To hope to find you listening for the door.

I stand in the ticking room. My dear, I take

A moth kiss from your breath. The shore gulls cry.

I leave this at your ear for when you wake.

The Indian Never Had A Horse by Etel Adnan

We burned our wings over

candles

in the alleys of Beirut

we played:

ball

hopscotch

cards

and love games

then we slept in the belly of

huge airplanes

flying over territories at war.

The poetry room is my favorite room at Perelandra. So much so that I hope to create a room similar in a home one day. The existence of that space is so comforting to me. I looked to see how early the shop opened so that I may come in and read there before work. Thank you for this look into the making of it. I hope to continue to enjoy the mysterious of it for years to come.