On March 30th, Indigo and I welcomed our daughter into the world. She has welcomed and wakened us, in turn, in ways I will not (yet) venture to express. However, I must thank you—thank you—for your camaraderie and support: here, in the disembodied bowels of culture, but especially where you are, working through meaning on your own terms.

I share the following metaphysical hash to signal my gratitude and the tenuousness of my digital involvement, for a time, in the hopes that you will forgive the lapses of this sleep-deprived bookseller. I hope some of these thoughts might land like fish on your mind’s line, and give you good strange dreams in the moons to come. —Joe

The Mayan shaman Martín Prechtel writes that in the Tzutujil language there is no word for door: “All Mayan houses are only one room. Their entrance is their mouth.” The doorway—chijay, “mouth of the house”—is integral to the ancient Mayan etiquette of hospitality, while a door is the picture of an impediment. “The concept of a door,” Prechtel concludes, “is outside of their paradigm.”

Why does it matter that there is a word for doorway but not for door? The word “paradigm” suggests an answer. It comes from the Greek elements para- “beside” + deiknynai “to show,” thus the sense of a pattern or example: “to show side by side.” When shown side by side, the body and the house do not (in the Mayan experience) evince barriers but passages; the Tzutujil language reflects a certain fidelity to the body as the permeable center of human experience and, concurrently, knowledge.

The Mayan source-body of the Tzutujil paradigm has been all but destroyed, a violence that led Prechtel to record his experience as shaman in writing. His decision to do so went against all traditional precedent, a precedent suffused with centuries upon centuries of outright awe for the power of language. Besides, to quote Timothy Mitchell, writing through a parallel colonial lens, of Arabic:

“The directness of the relationship with Allah through the Word and its intensely abstract, intensely concrete force is extremely difficult to evoke, let alone analyze for members of societies dominated by print and the notion of words standing for things.”

Today, given prodigious technological advancements, it would seem that we have great opportunities to effect changes in perception. But these great opportunities belie great fears, which challenge everything we know from within.

One of my great fears is exposure: being revealed for the small and unfinished being that I am. And writing—like this—looks a lot like an attempt at indulging or delimiting said fear. The real question is: What is one imperfect person to do with something as powerful as language?

If writing and reading are the hemispheres of language-as-literature, the above fear reflects an incomplete view of things, a view that mirrors the incompleteness of any being such as “me.” This fear is abolished—the hemispheres reconciled—by the perception of passage: from one thing to another: from beyond the threshold to inside the sanctuary.

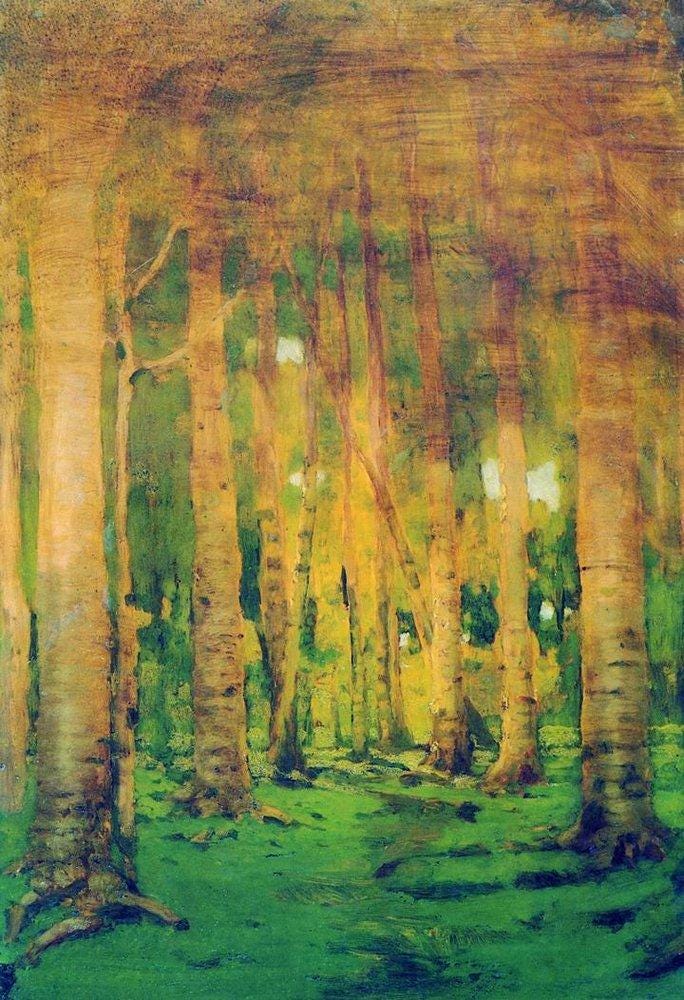

So, in writing I fear, but in reading—Prechtel, Abram, Baldwin, Benjamin, Barthes, Dickinson, Le Guin, Lewis, Rilke, Ruefle, Snyder, et al.—I am given to understand that my fear is analogous with the awesome contingency of the self, and this analogy is a doorway to understanding that I am nothing if not relational. The space between two hands—two lips—is awe, the gasp or grip that precipitates A-U-M. It is a fearsome topology.

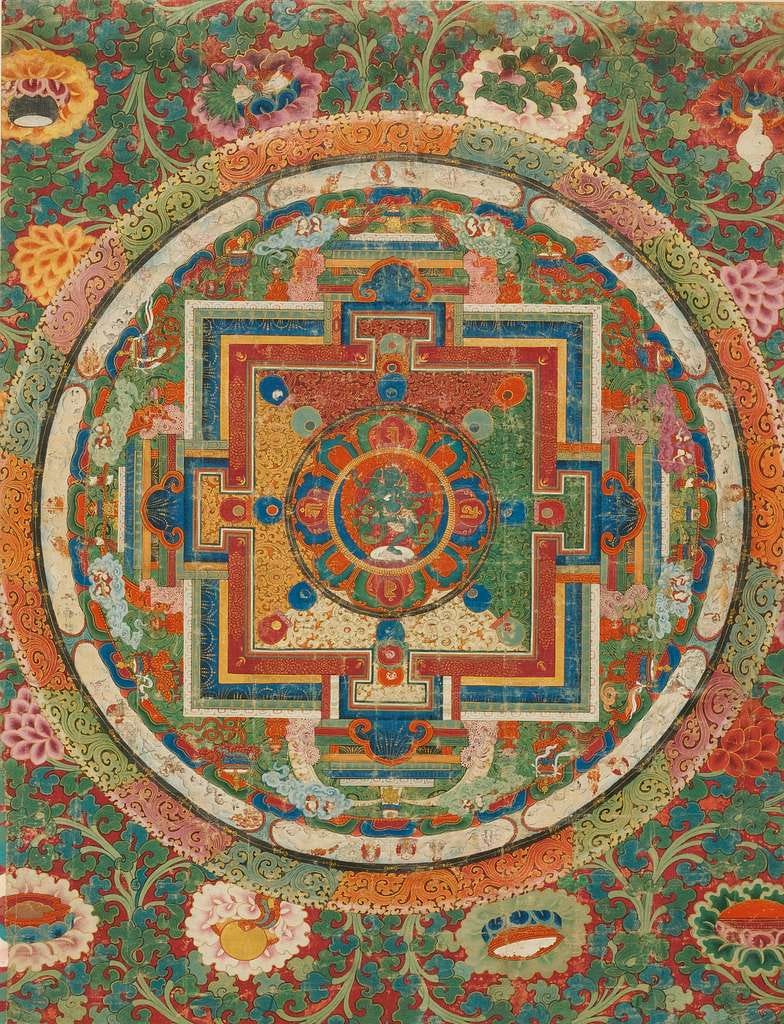

BILL MOYERS: Explain “Aum.” That’s the first time you’ve used that.

JOSEPH CAMPBELL: Well, “Aum” is a word that, what can I say, represents to our ears that sound of the energy of the universe, of which all things are manifestations. And “Aum”, it’s a wonderful word, it’s written A-U-M. You start in the back of the mouth, Ah, and then, Ooh, you fill the mouth, and M-m-m, closes it, the mouth. And when you have pronounced this properly, all vowel sounds are in that pronunciation: “Aum”. And consonants are regarded simply as interruptions of “Aum”, and all words are thus fragments of “Aum”, as all images are fragments of the form of forms, of which all things are just reflections. And so “Aum” is a symbol, a symbolic sound, that puts you in touch with that throbbing being that is the universe.

And when you hear some of these Tibetan monks that are over here from the Rgyud Stod monastery outside of Lhasa, when they sing the “Aum,” you know what it means, all right That’s the zoom of being in the world. And to be in touch with that and to get the sense of that, that is the peak experience of all. “Ab-ooh-mm.” The birth, the coming into being, and the solution to the cycle of that. And it’s just called the four-element syllable. What is the fourth element? “Ah-ooh-mm,” and the silence out of which it comes, back into which it goes, and which underlies it.

Now, my life is the “Ah-ooh-mm,” but there is a silence that underlies it, and that is what we would call the immortal. This is the mortal, and that’s the immortal, and there wouldn’t be this if there weren’t that.

BILL MOYERS: The meaning is essentially wordless.

JOSEPH CAMPBELL: Yes. Well, words are always qualifications and limitations.

BILL MOYERS: And yet, Joe, all we puny human beings are left with is this miserable language, beautiful though it is, that falls short of trying to describe…

JOSEPH CAMPBELL: That’s right. And that’s why it’s a peak experience to break past all that every now and then, to realize “oh, ah,” I think so.

Personhood is an inherently public, fundamentally common constitution. So, is there any privacy—any peace—to be had in living? Silence and solitude undo all reassurance; the more silent one becomes, the louder the signification of one’s surroundings. Prayer becomes performance of the highest order: performance before the gods and for one another.

“Our family is looking / for someone who knows how to pray,” Annie Dillard writes in the final, titular poem of Tickets for a Prayer Wheel. I take “our family” in the largest sense—larger, even, than the human species. And I think that we are basically surrounded by Someone: she is the person with whom we are fortunate enough to interact as we wake to the duties of the day.