Reading and the will to live

On the idea of consuming language and being consumed

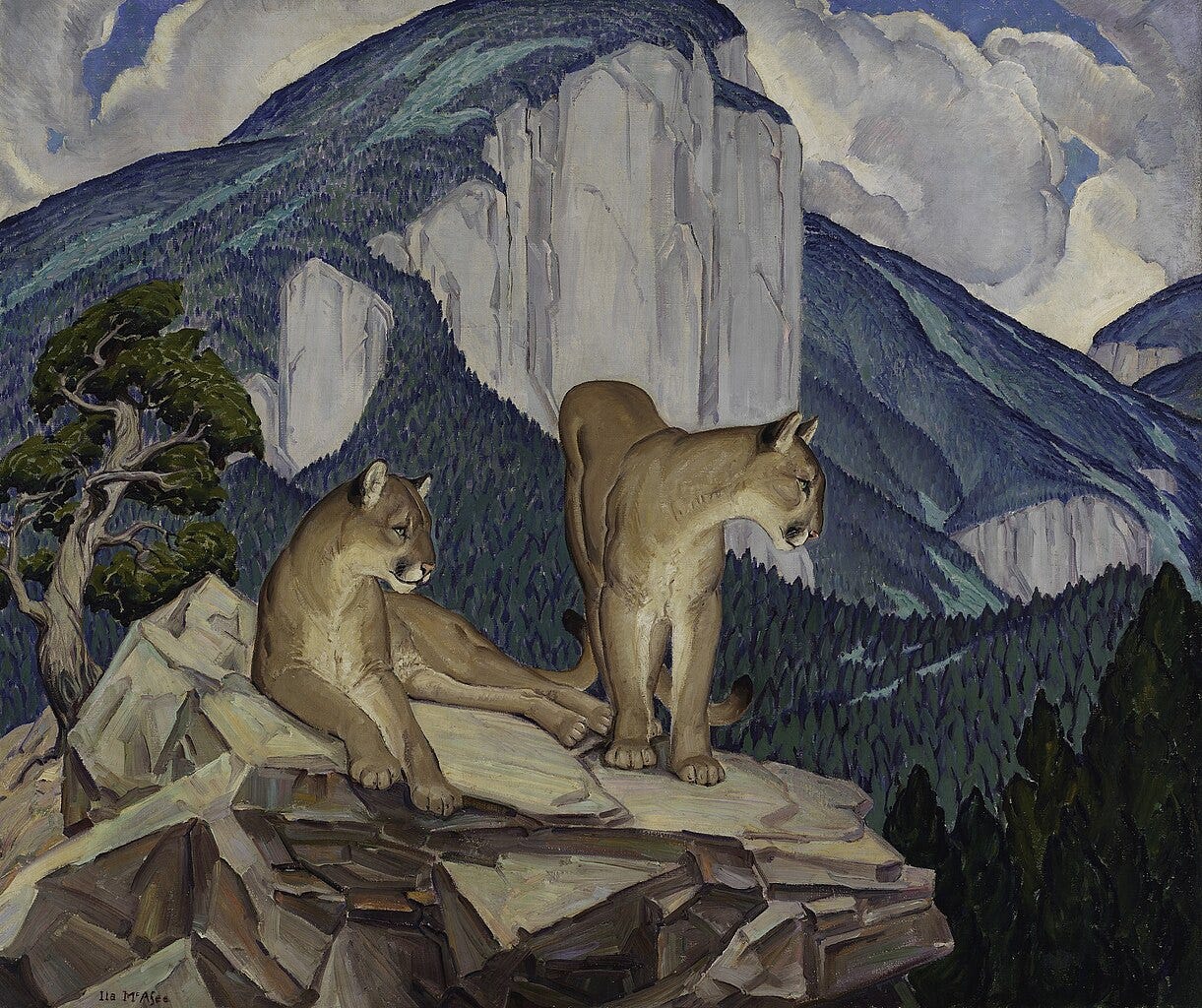

When I return home from a hike to the ridge, I’m always a little disappointed that I didn’t get eaten by a mountain lion. I know this sounds facetious, and to some extent it is—who in their right mind would want to be eaten by a mountain lion? But under the surface of my absurd Thanatos1 is a perplexing and irrevocable truth.

According to my friend Cookie, the truth is that when I go forth into the wild world, I want to be changed. It’s a simple yet extraordinarily salient point that describes a desire—the shell of a tender ancient need—embedded in sentience itself: to be (or become) more than oneself.

As regards the deadly encounter with a mountain lion (or any other agent or area of existential transfiguration), the desired change resembles metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls, and metempsychosis—per my skewed theological calculus2—recalls transubstantiation.

Metempsychosis proceeds from the ancient Greek notion of the body and soul as separate but contractually bound to one another unto death (which “dissolves the contract”), at which point the soul is re-bodied, “for the wheel of birth revolves inexorably.”3

Transubstantiation, on the other hand, is a sacramentally specific undertaking (and understanding) of a similar event, namely the mystical transmutation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. “Catholics believe that when one consumes the Eucharist,4 one is incorporated into Christ and becomes bonded to others who are also part of the body of Christ on Earth.”5

There’s a lot to digest here (pun intended), but the bottom line, to my mind, is that the nature of substance is to move between bodies. How, then, do we separate life from life, lives from living? What really distinguishes the life that receives from the life that offers? What—refracting this question through literary practice—is the difference between reading (receiving) and writing (offering)?

The answer, I sense purring in the feline-dark recesses of my unutterable self, has something to tell us about our needs and desires: our hunger: the impulses that keep us—at the expense of many other forms of being—alive.

On second thought, maybe the questions I am really trying to ask are not objective and differentiating but moral and ultimate: Is life good? Are reading and writing good? Is the mountain lion bad for wanting to eat me? Or am I bad for wanting the mountain lion to eat me?

If I’m jumping around a bit here, it can’t be helped—I’m looking for a stable spot from which to leap off into the deeper-than-deep end. Which reminds me of a lune I wrote a while ago, called “Depends”:

deep ends deep

ends deep ends deep ends

deep ends deep

Something about the homophone introduces this profound vacillation between one sort of fathom (depth) and another (finality). The back-and-forth resembles the paradox of simultaneously wanting to be eaten and wanting to survive. It’s like vertigo, which incidentally shares the same Proto-Indo-European root as the words verse and worry: *wer- “to turn, bend.”

I reckon that the writer writes to make the imaginary of their experience legible. In other words, the writer writes in order to read. Ah, but here’s the catch: the writer also writes in order to be read. The producer is never more than the consumer, and never less.

Writing and reading, eating and being eaten—all of it laced and surrounded by feelings of trepidation and sacrilege. I take solace, as many millions have, in Mary Oliver’s conviction: “You do not have to be good… You only have to let the soft animal of your body / love what it loves.”

But in truth, there’s one more thing you have to do. You have to let the soft animal of other bodies love you back.

*

Thanks for sticking with me here, folks. Spring is a beautiful and challenging time; the courtyard is again bursting with people, and yet the numbers are just as tight as ever. I don’t like to admit this, because it feels like I should just do better. But capitalism is challenging when expansion is not an agreeable outcome.

What I mean to say is that I am grateful for your attention and support. Just like I’m not capable of selling books for the sake of sales, I’m not capable of generating language for the sake of subscriptions. I hope the slow schedule of material here meets you where you are, and gives you something to chew on (*wink wink*). The regular monthly Cairn will land in your inbox soon. — Joe

Thanatos, the mythic Greek personification of death, is synonymous with what is called (in a “post-Freudian” psychological landscape) a death wish or death drive.

I’ve swiped and adapted this phrase from the magpie scholar herself, Anne Waldman, in Vow to Poetry (2001): “By my own skewed associational mathematics, Vow = Voice. I vote always for the transforming of language’s energy side with a full voice.”

It’s important to note that this transaction, so to speak, is not limited to the human species—souls can transmigrate from human to animal and vice versa.

Eucharist is a word derived from the Greek eukharistos, meaning ‘grateful,’ and implies the goodness or grace of an offer well received.