Reading for joy takes practice

On the nature of interest (and the virtues of eavesdropping)

Eavesdropping is not a particularly commendable activity, for the dropper of eaves listens in secret and in snatches, with a necessarily limited (or, in the spy’s case, preordained) sense of context. But when one speaks of books within earshot of a bookseller, well, one might as well be in a confessional talking about the devil. Mea culpa.

I was pricing books upstairs from the frosty hours before open to the warmer mid-morning when visitors arrive to look around or settle in. Two folks in the latter category sat down near me, talking first of breakfast and then—as more people came upstairs to browse the shelves—of reading books.

“I start a book I’m really excited about and then just, like, lose interest immediately.”

I hear this sort of thing said, in different words, all the time. There was a note of defiance in this one’s voice, but in most cases it comes out sounding confessional and abashed, if not outright apologetic.

It’s a familiar, systemic sadness, this feeling of not (or no longer) having what it takes to appreciate a book, yet we tend to feel personally deficient. The shame reinforces our perceived alienation, which begins to look like the natural order of things.

What I wanted to say to the person I overheard—and what I am instead relating here—is that interest develops in and over time, with natural fluctuations of gain and loss. Taking interest in something is a brief, wonderful, dopamine-inflected part of the process; being interested is the process at large.

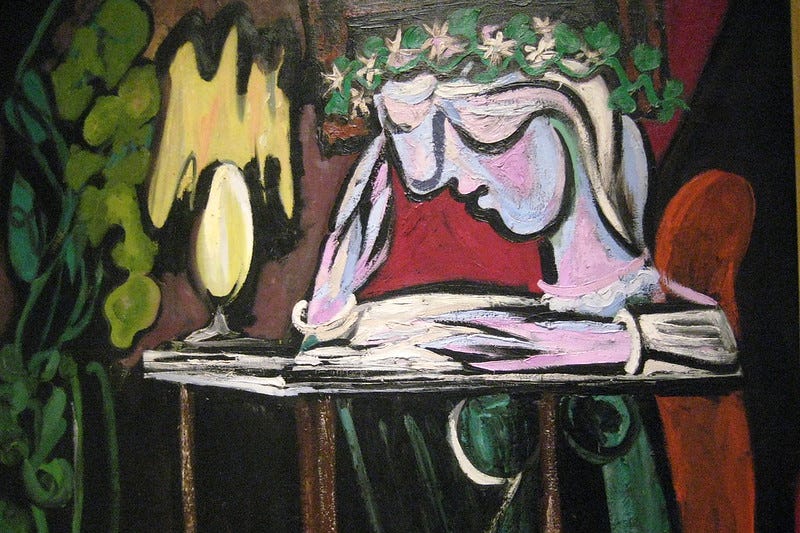

A book is fundamentally contingent on the process of reading it.1 Which is to say that the loss of interest in a book is a loss of interest in the experience of reading a book: the tranquil posture and practiced intellection, imagination, and empathy.

The stuff that makes a book interesting exists in the time-space of the book; try as we might to parse and preserve this stuff—to find “the point”—it cannot be done.2 Life is a wavy line; we must find the point anew, every step and stroke of the billowing way.

Reading for “the point” (datum, info) is now a Google search away, requiring little more from us than a tic. Reading for joy (love, understanding) takes rhythm.

In a book, your attention as a reader is the thing that makes it go, and it is—unlike the so-called choices proffered by apps and channels, comments and likes—yours: not just the capacity to receive and respond to information, but to move toward it.3

On a separate philosophical note: I suspect that the conversation I overheard upstairs turned to books not because the two friends decided to talk about their reading lives, but because they existed in a contingent space and were in some sense responding to the space itself, replete as it was with cohabitants (animate and inanimate).

This was the beginning-place of something I’ll call radical responsibility, but it flinched at the prospect of solitude, receding within the technologically-reinforced shell of visual kinesis and personal preference: volition reduced to vote.

For it is not just the choices we make, but the time they take and the space they hold that matter.

To be continued…

A book is borne of experience, the reading-writing continuum. Market valuation challenges this, as exceptionally “valuable” books—like their counterparts in visual art—increasingly resemble pure investments, sequestered in behind glass or concrete.

Of course it is done, as a matter of criticism or analysis or exchange, but it remains contingent. Christian Wiman recently explored the poetics of this tendency: “I am drawn, like any ‘common reader,’ to poems that reach for succinct and universalizing statements... ‘Hope not being hope / until all ground for hope has / vanished’ (Marianne Moore). ‘The end of art is peace’ (Seamus Heaney). ‘We are what we are only in our last bastions’ (me). Removed from the flesh of their poems, though, the statements become a bit bony and cold. They don’t pierce or reverberate; they thud and nag. The end of all art is ‘peace’? Can we really have no understanding of hope or identity until those things have been crushed? Do we love truly only when we feel fully the ultimate futility of such love?” (The American Scholar, Autumn 2023)

Re: attend, from Latin attendere “give heed to,” literally “to stretch toward” (ad- “to, toward” + tendere “stretch”)

To stretch toward - both the reader and the writer - through time and space to something beyond both of them. Thank you for cultivating a connecting space - -and keep these posts coming!