The limits of logistics, revisited

Amazon, Alphabet, and the conscription of consciousness

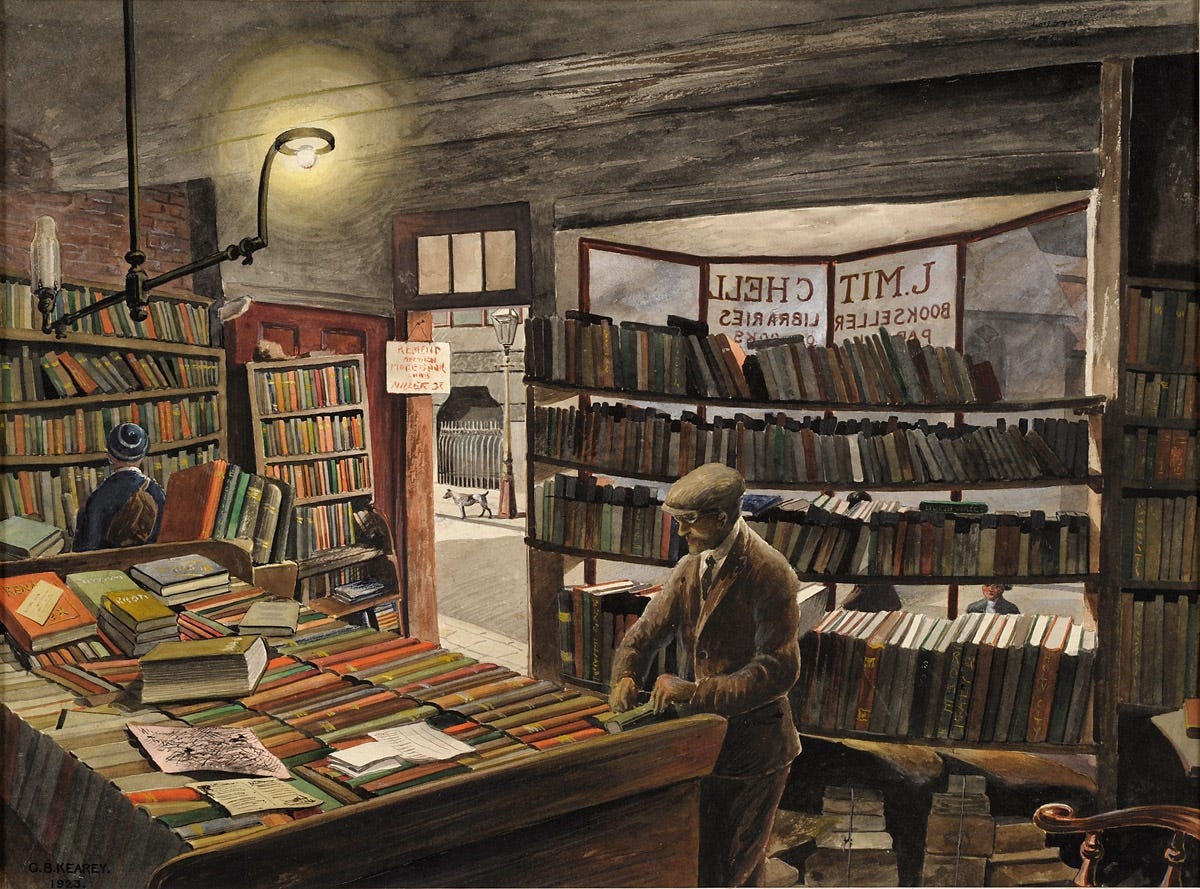

Two years ago, I shared the following reflection on bookselling as it relates to information technology, and what this relationship portends for Perelandra. I resend it now in the manner of renewing my vow to the bookshop, and in the hope that it gives you courage heading into the new year.

Note: Jeff Bezos’s net worth “as of this writing” pertains to a publication date of January 2023. His net worth today, two years later, is double. — Joe

In a sardonic little essay published on the ambitious, regrettably patronizing platform, Unherd (“We hope you find something that makes you think again”), the brilliant writer Paul Kingsnorth refers to Jeff Bezos as a “glorified bookshop manager”:

Most of all, a great disappointment seemed to spread like an ink stain through the remnants of the West, as it dawned on everyone that there was to be no spectacular denouement… The best anyone could manage at this point in industrial capitalism’s downward curve was a weedy little spaceship built by a glorified bookshop manager, which could stay up in space for all of three minutes. The end of the world, it turned out, was less like Terminator and more like a Star Wars prequel: you wait for years in anticipation, and then it’s just a let-down.

Setting aside, for a moment, the larger philosophical context in which it is couched, the bookshop manager comment is spot on. Before becoming The Everything Store, Amazon was an online marketplace for books. It’s a bewildering lineage: The invention of the book (or codex) precipitated the inception of modern logistics, which begot the modern computer, which is the infrastructural basis of this very engagement, among too many others over the course of our screen-saturated days.

The cultural historian might ask: At what point do (or did) we become religious about logistics? Surely it was before Amazon clearcut the rainforest of our imaginations,1 and well before the googol power of Google was reconstituted as a unilateral Alphabet. Pagination, for one, meant that we didn’t need to be quite as devotional about the record of the past, however poetic or practical its information. Pre-codex, think: Hours of daily recitation unto memorization of scores, maybe hundreds of scrolls of scripture, a practice endemic to every “church” in the world, from Lhasa to Chartres. Reading is the root of religion.2

The bookseller in me asks: To what extent does the logistical imagination serve a space whose business (and cultural mission) is fostering and sustaining encounters with literature? The advent of the codex enabled the tracking of financial obligations—represented by paper money, or promissory notes, beginning in the 8th century—occurring over years and, eventually, generations; leap ahead to the 20th century, and computation (data storage, memory, etc.) has enabled accounting that is an order of magnitude more complex.

How much and what sort of computational power is necessary to hold space for the codex as narrative object and cultural encounter?

As Amazon “the online marketplace for books” gradually became The Everything Store, it failed as a literary community. And while most people wouldn’t look at Jeff Bezos—worth all of $120 billion as of this writing3—and think, “now that’s a man whose business has failed,” that is exactly the point we should glean from Kingsnorth’s mockery.

The “glorified bookshop manager” comment has proven uniformly perturbing to friends with whom I’ve brought it up. “Jeff Bezos isn’t a bookshop manager” is the consensus, and “you’re nothing like Jeff Bezos” is the refrain. I’m grateful that my community is repulsed by the idea of associating me with the world’s most notorious capitalist. But I’m equally perturbed by the opacity of bookselling’s logistically entrenched mores. Hence this dispatch.

Bookselling is central to the economic praxis that gave us the digital marketplace. But, occupationally speaking, it doesn’t need to abide the logics of digital computation any more than a codex needs to be full of numbers and not poetry.

In conclusion, I want to briefly explain three foundational approaches to logistics at Perelandra—how these idiosyncratic, anachronistic strategies help 1) maintain retail operations with a nuanced understanding of profit, 2) refuse the false-premise that Perelandra is competing with Amazon, and 3) keep me from turning into Jeff Bezos, or doing business in ways that dehumanize myself or others.

Alphabetical disorder - Conventional wisdom holds that the best way to find particular titles is to keep them alphabetized (by author’s last name). But there are other, more organic ways to constrain or limit the territory a given book may inhabit, which is fundamentally what alphabetization does. Furthermore, strict alphabetization consigns particular authors to be in the same vicinity, forever; it’s as if the chimpanzee was destined to always live next to the chinchilla. Differential order abides the fact that books are more than the sum of their authors’ identities.

Reimagined genre - When genre is reimagined, the physical geography of a bookstore changes in unpredictable but recognizable ways. New, hybrid genres are no less identifiable than conventional ones, and an abundance of genres—like species—leads to more diverse, particular, and distinct dynamics. It’s all exceedingly memorable, whereas a space limited to conventional genre hinges on alphabetization and computation. A book in a wild environment is replete with sentience. Booksellers and customers alike need only use their senses.

Inventory friction - We log book sales by hand, which means that we cannot automatically re-order books that have sold (as in click “order” on a list populated by the previous week’s sales data); even perennial bestsellers must be considered against the shop’s ever-evolving ecosystem of literature. This satisfies the needs of new and repeat customers, alike. Plus, in writing the title, author, and price of someone’s book purchase on a sheet, the hand recovers its primary agency in the legibility of one’s life.

As so-called consumers, our instincts and tendencies have evolved over millions of years. And while the tech industry is busy “hacking” dopamine levels, it’s quickly realizing that the brain is not the only thing about us that governs behavior. Like the book is more than its author, the body is more than its brain; intelligence is situated in the whole being, or nowhere.

When I look at the burgeoning metaverse with virgin eyes, I see corporations quixotically attempting to maintain power over the human body. Maybe we will all eventually have professional avatars that walk under cold white pixelated stars to the pathological droning of our administrative superiors, and despair.

Meanwhile, I’ll relish the mental stimulation, physical serendipity, and emotional spontaneity of being my own search engine, and watching my community respond to the bookshop with genuine agency and compassion. And though occasionally lost, we will be found. We will not want for fellow seekers in this strange and shifting world.

The name Amazon (Amazonas) was colonially ascribed to the rainforest and biosphere by conquistador Francisco de Orellana, who waged war against the indigenous Tapuya people, among others. [→]

c. 1200, religioun “state of life bound by monastic vows,” from relegere “go through again” (in reading or in thought), from re- “again” + legere “read” (see: lecture); also connected with religare “to bind fast,” as in “place an obligation on,” or “bond between humans and gods.”

January 2023. As of January 2025, it is $240 billion